The Most Significant Change to AML Rules Since the USA Patriot Act

Insights  Thomas Fawell · January 4, 2021

Thomas Fawell · January 4, 2021

Overview.

January 2, 2021. The newly enacted National Defense Authorization Act[1] (NDAA) imposes the most significant reformation of the Bank Secrecy Act (BSA) and related anti-money laundering (AML) laws since the adoption of the USA PATRIOT Act. The largest changes are in division F, the Anti-Money Laundering Act of 2020 (the “Act”). The general intent of the Act is to expand the AML focus from a domestic regulatory regime to one focused on international money movements and collaboration with law enforcement – all built upon stronger technology and analytics. A central component of this new focus is a mandate to compel the disclosure of ultimate beneficial owners of shell companies that have historically served as the tools of money launderers, terrorist financiers, sex traffickers, and assorted other malign actors.

To achieve its objective, the Act casts a very wide net targeted to identify the intended obscure Russian oligarch. However, this well-intended net will also compel the membership disclosure of your Uncle Maury’s new LLC. Congressional comments note that compliance is expected from approximately 30 million existing corporate entities in the US as well as new US entities estimated at 2 million annually.

International Comparison.

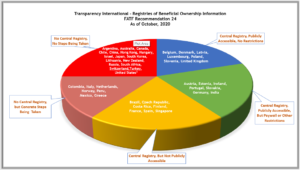

Most of the EU, as well as a number of Latin American countries and India have some sort of ultimate beneficial ownership disclosure requirement. Since 2009, Representative Carolyn Maloney (D. NY) has unsuccessfully advocated the current bill in its present form. What changed her 2009 aspiration into 2020 law was the support of the current administration. As confirmed by the override of the Presidential veto, this bill enjoys broad bipartisan support.

In comparison to other countries, the U.S. has chosen a moderate path that requires disclosure to the Treasury and Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN), but otherwise maintains confidentiality of all such information in a manner similar to the confidentiality maintained in the storage and management of tax information by the IRS. Hence, unlike many EU countries, beneficial ownership information of US entities will not be made publicly available, but will only be available to law enforcement on a selective basis.

Who Must File And Comply.

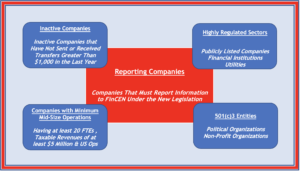

The Act requires “Reporting Companies” to inform FinCEN of their beneficial owners. That term, “Beneficial Owner” carries a familiar definition of any person who, directly or indirectly, (i) owns 25% of the equity interests or (ii) exercises “substantial control” over the entity. While the term “substantial control” is not defined, the congressional comments anticipate that FinCEN regulations will adopt an ancillary FinCEN definition of “…a single individual with significant responsibility to control, manage, or direct a legal entity customer”. “Reporting Companies” is more precisely defined as virtually any corporation, LLC, or other entity, whether domestic or foreign that is authorized to do business in the US. However, this definition is subject to two very broad exceptions. They are:

- Entities that are either inactive or already subject to some level of government scrutiny such as 501(c)(3)s, banks, FinCEN registered money transmitters, SEC-registered broker-dealers, SEC-registered investment advisers, and a variety of other governmental and quasi-governmental entities, etc.

- Oddly and without explanation, an exception was given to companies (i) with more than 20 FTEs, (ii) that report revenue to the IRS of more than $5M; and (iii) that have an operating presence within the U.S.

The division of “Reporting Companies” from non-reporting companies is fairly depicted in the following diagram:

Elements of compliance

Required Information. The FinCEN forms will require each applicant to identify each beneficial owner of the applicable reporting company by providing (i) the full legal name of the beneficial owner; (ii) the date of birth; and (iii) the current, as of the date on which the report is delivered, residential or business street address. The ”applicant” will also be required to file (i) the very same information as if the applicant were a beneficial owner, and file (ii) a unique identifying number from an acceptable identification document (e.g., passport number), or alternatively, a “FinCEN identifier”.

Applicant. Consistent with an underlying thesis of full transparency, the Act requires that the “applicant” be a living, breathing person and not an entity. The specific language of the Act defines an applicant as “…any individual who (A) files an application to form a corporation, limited liability company, or other similar entity under the laws of a State or Indian Tribe; or (B) registers or files an application to register a corporation, limited liability company, or other similar entity formed under the laws of a foreign country to do business in the United States by filing a document with the Secretary of State or similar office under the laws of a State or Indian Tribe.”

FinCEN Identifier. The Act anticipates that FinCEN will issue identifying numbers (”FinCEN Identifiers”) similar to the function provided by the IRS in the issuance of FEINs. The FinCEN identifiers will be issued to both individual applicants as well as reporting entities.

The Time to Report. The Act requires the first draft of regulations to be completed within one year of its adoption. Existing reporting companies will have one year thereafter to comply and report. New formations will have to report beneficial interest at time of formation. For all others, changes in beneficial ownership must be reported within a year. FinCEN’s regulatory scope will likely provide additional specific guidance.

Enhanced Technology, Enforcement and Pain. The aspirational language of the Act directs FinCEN, the Treasury and DOJ to enhance technology to identify patterns associated with illicit activity. In a separate sections, the Act’s aspirational language directs agencies’ and departments’ consideration of certain particular verticals of crypto currencies, antiquities, and art – all historical tools of malign actors. When these disparate pieces are considered as a whole, the Act anticipates that enhanced Artificial Intelligence will become a significant tool in the identification of criminal activity. This is not quite the equivalent of anticipatory arrests depicted in the futuristic film Minority Report, but will certainly equip law enforcement to employ AI in the identification of otherwise undetected criminal activity.

To assure proper incentives, the Act imposes a range of harsh penalties ranging from entity profit forfeiture, to bonus claw backs for the unintentional but consequential lapse of compliance. Where non-compliance becomes repetitive or transcends from the unintentional error to intentional violation, the Act provides for criminal penalties, enhanced fines, and the barring individuals from serving on the boards of U.S. financial institutions.

Considerations of Foreign Capital Investment in the U.S.

While the act does not expressly target foreign investment, it does highlight particular events more common to inbound foreign investment.

DOJ Subpoena Power of Foreign Banks. In keeping with the international focus of the Act, § 6308 broadly expands DOJ’s power of subpoena with respect to foreign banks. Current law allows DOJ to subpoena a US bank for records of any correspondent account. This revised section now empowers DOJ to subpoena “any records relating to the correspondent account or any account at the foreign bank, including records maintained outside the United States” (emphasis added).

Moreover, similar to SARs (Suspicious Activity Reports), §6308(a)(3)(C)(i) precludes officers, directors, attorneys, or other agents of the foreign bank from directly or indirectly advising a customer that a subpoena has been issued. The clear cautionary direction to the offshore client is that lack of compliance, or even falling within an algorithmic area of discovery, could open the account and the client to unwelcomed and undetected scrutiny.

Politically Exposed Persons (PEPs) and Senior Foreign Political Figures (SFPFs)

PEPs[3] and SFPFS (31 CFR § 1010.605) are accorded special attention in § 6313. The section provides that “No person shall knowingly conceal, falsify, or misrepresent, or attempt to conceal, falsify, or misrepresent, from or to a financial institution, a material fact concerning the source of funds in a monetary transaction that is… (i) one million dollars or greater and (ii) affects interstate commerce.”

Penalties for infractions are graciously limited to not more than 10 years in prison and not more than one million dollars. A culpable “person” need not be a member or shareholder officer, but could include outside counsel or anyone found to be part of a conspiracy of misrepresentation.

Conclusion

Like most modern legislation, the Anti-Money Laundering Act of 2020 is aspirational, deferring specific terms to later agency regulation. Such aspirational language is unmistakable and identified with phrases like “the sense of the Congress is…”. Notwithstanding the mandate to deliver regulations in the coming year, the experience of the Patriot Act suggests that the primary scope of regulatory activity will consume at least three years after adoption.

In summary, the Act portends an enforcement mechanism that is much broader in scope and current law, with more specific information requirements and more sophisticated methodologies. This broader scope will likely mature in three identifiable ways:

- The regulatory effort will further tighten rules regarding the identification of ultimate beneficial owners. Even a casual reading of the many exemptions for non-reporting companies will identify paths of circumvention. A careful attorney should anticipate that those paths of circumvention will be closed by regulation in the coming year.

- The clear intent of the aspirational language is that of an international focus, directed with particularity to PEPs and to SFPFs. Inbound capital will garner particular scrutiny.

- DOJ, Treasury, and affiliated agencies will invest heavily in new technology to meet the Act’s express intent to implement technology and artificial intelligence to combat money laundering. To assure compliance, the Act requires relevant agencies to report annually to Congress regarding the strength and robust nature of technology in combatting money laundering.

Investors, managers, directors, and all interested parties should understand that the notoriety accorded money laundering, particularly post the Panama papers, has built a strong bipartisan consensus in the US lawmakers and agencies. Accordingly, the Act is here to stay and will be enforced.

[1] On January 1, 2021, the Senate voted 81-13 to override the President’s veto, exceeding the two-thirds supermajority required. The action follows the House’s 322-87 override on Monday, and the bill now becomes law.

[2] With the veto override of January 1, 2020, the U.S. has moved from the red section “No Registry, No Steps Being Taken”, to the yellow section “Central Registry, But Not Publicly Available”.

[3] The term “Politically Exposed Persons” or “PEPS” is a generic term not defined in the Bank Secrecy Act or in Federal regulations. On August 21, 2020, the Office of Comptroller of the Currency issued a joint statement with other agencies that adopted the common generic definition defining “PEPs” (i) first negatively as a person exclusive of US political figures, and (ii) positively as “…foreign individuals who are or have been entrusted with a prominent public function, as well as their immediate family members and close associates.” (emphasis added). Joint Statement (fincen.gov)

Thomas Fawell practices in the areas of mergers & acquisitions and capital formation, inclusive of 1940 Adviser Act compliance and real estate finance and development. Before Rimon, Mr. Fawell served as Partner and Member of the Management Committee at Katten Muchin.

Mr. Fawell’s deep experience includes advising collectors in multiple art transactions strategies, as well as business owners and real estate developers through multiple funding alternatives and structures, acquisitions, dispositions, capital formation, and joint ventures, identifying risks and benefits of competing interests. Read more about Tom here.

Attorney Advertising. This document is not intended to be and is not considered to be legal advice. Transmission of this document is not intended to create, and receipt does not establish an attorney-client relationship. Prior results do not guarantee a similar outcome.